The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan is a small, young country located on land of ancient biblical significance. The country is one of the most liberal in the region and also has one of the smallest economies, as it lacks the natural resources enjoyed by many of its neighbors.

Jordan is situated at the crossroads of Asia, Africa and Europe, within the levant region, on the East Bank of the Jordan River. Jordan is bordered by Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Syria, Israel and the West Bank of Palestine. The Dead Sea is located along its western borders, and the country has a 26-kilometre (16 mi) coastline on the Red Sea in its extreme south-west. Amman is the nation's capital and largest city, as well as the economic, political and cultural centre.

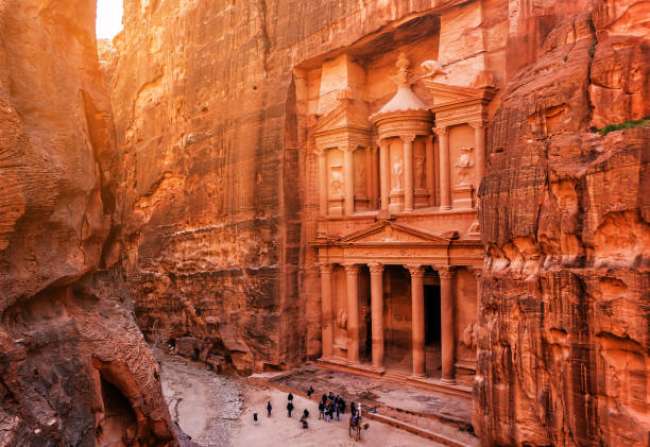

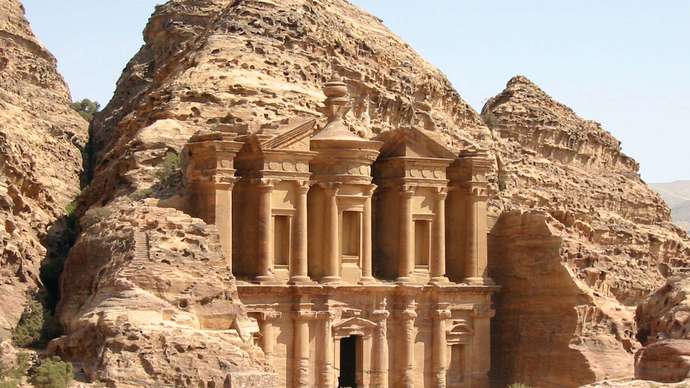

Jordan is a young state that occupies an ancient land, one that bears the traces of many civilizations. Separated from ancient Palestine by the Jordan River, the region played a prominent role in biblical history. The ancient biblical kingdoms of Moab, Gilead, and Edom lie within its borders, as does the famed red stone city of Petra, the capital of the Nabatean kingdom and of the Roman province of Arabia Petraea. British traveler Gertrude Bell said of Petra, “It is like a fairy tale city, all pink and wonderful.” Part of the Ottoman Empire until 1918 and later a mandate of the United Kingdom, Jordan has been an independent kingdom since 1946. It is among the most politically liberal countries of the Arab world, and, although it shares in the troubles affecting the region, its rulers have expressed a commitment to maintaining peace and stability.

The capital and largest city in the country is Amman—named for the Ammonites, who made the city their capital in the 13th century BCE. Amman was later a great city of Middle Eastern antiquity, Philadelphia, of the Roman Decapolis, and now serves as one of the region’s principal commercial and transportation centres as well as one of the Arab world’s major cultural capitals.

Land

Slightly smaller in area than the country of Portugal, Jordan is bounded to the north by Syria, to the east by Iraq, to the southeast and south by Saudi Arabia, and to the west by Israel and the West Bank. The West Bank area (so named because it lies just west of the Jordan River) was under Jordanian rule from 1948 to 1967, but in 1988 Jordan renounced its claims to the area. Jordan has 16 miles (26 km) of coastline on the Gulf of Aqaba in the southwest, where Al-ʿAqabah, its only port, is located.

Relief

Jordan has three major physiographic regions (from east to west): the desert, the uplands east of the Jordan River, and the Jordan Valley (the northwest portion of the great East African Rift System).

The desert region is mostly within the Syrian Desert—an extension of the Arabian Desert—and occupies the eastern and southern parts of the country, comprising more than four-fifths of its territory. The desert’s northern part is composed of volcanic lava and basalt, and its southern part of outcrops of sandstone and granite. The landscape is much eroded, primarily by wind. The uplands east of the Jordan River, an escarpment overlooking the rift valley, have an average elevation of 2,000–3,000 feet (600–900 metres) and rise to about 5,755 feet (1,754 metres) at Mount Ramm, Jordan’s highest point, in the south. Outcrops of sandstone, chalk, limestone, and flint extend to the extreme south, where igneous rocks predominate.

The Jordan Valley drops to about 1,410 feet (430 metres) below sea level at the Dead Sea, the lowest natural point on Earth’s surface.

Drainage

The Jordan River, approximately 186 miles (300 km) in length, meanders south, draining the waters of Lake Tiberias (better known as the Sea of Galilee), the Yarmūk River, and the valley streams of both plateaus into the Dead Sea, which occupies the central area of the valley. The soil of its lower reaches is highly saline, and the shores of the Dead Sea consist of salt marshes that do not support vegetation. To its south, Wadi al-ʿArabah (also called Wadi al-Jayb), a completely desolate region, is thought to contain mineral resources.

In the northern uplands several valleys containing perennial streams run west; around Al-Karak they flow west, east, and north; south of Al-Karak intermittent valley streams run east toward Al-Jafr Depression.

Soils

The country’s best soils are found in the Jordan Valley and in the area southeast of the Dead Sea. The topsoil in both regions consists of alluvium—deposited by the Jordan River and washed from the uplands, respectively—with the soil in the valley generally being deposited in fans spread over various grades of marl.

Climate of Jordan

Jordan’s climate varies from Mediterranean in the west to desert in the east and south, but the land is generally arid. The proximity of the Mediterranean Sea is the major influence on climates, although continental air masses and elevation also modify it. Average monthly temperatures at Amman in the north range between 46 and 78 °F (8 and 26 °C), while at Al-ʿAqabah in the far south they range between 60 and 91 °F (16 and 33 °C). The prevailing winds throughout the country are westerly to southwesterly, but spells of hot, dry, dusty winds blowing from the southeast off the Arabian Peninsula frequently occur and bring the country its most uncomfortable weather. Known locally as the khamsin, these winds blow most often in the early and late summer and can last for several days at a time before terminating abruptly as the wind direction changes and much cooler air follows.

Precipitation occurs in the short, cool winters, decreasing from 16 inches (400 mm) annually in the northwest near the Jordan River to less than 4 inches (100 mm) in the south. In the uplands east of the Jordan River, the annual total is about 14 inches (355 mm). The valley itself has a yearly average of 8 inches (200 mm), and the desert regions receive one-fourth of that. Occasional snow and frost occur in the uplands but are rare in the rift valley. As the population increases, water shortages in the major towns are becoming one of Jordan’s crucial problems.

Plant and animal life

The flora of Jordan falls into three distinct types: Mediterranean, steppe (treeless plains), and desert. In the uplands the Mediterranean type predominates with scrubby, dense bushes and small trees, while in the drier steppe region to the east species of the genus Artemisia (wormwood) are most frequent. Grasses are the prevalent vegetation on the steppe, but isolated trees and shrubs, such as lotus fruit and the Mount Atlas pistachio, also occur. In the desert, vegetation grows meagrely in depressions and on the sides and floors of the valleys after the scant winter rains.

Only a tiny portion of Jordan’s area is forested, most of it occurring in the rocky highlands. These forests have survived the depredations of villagers and nomads alike. The Jordanian government promotes reforestation by providing free seedlings to farmers. In the higher regions of the uplands, the predominant types of trees are the Aleppo oak (Quercus infectoria Olivier), the kermes oak (Quercus coccinea), the Palestinian pistachio (Pistacia palaestina), the Aleppo pine (Pinus halepensis), and the eastern strawberry tree (Arbutus andrachne). Wild olives also are found there, and the Phoenician juniper (Juniperus phoenicea L.) occurs in the regions with lower rainfall. The national flower is the black iris (Iris nigricans).

The varied wildlife includes wild boars, ibex, and a species of wild goat found in the gorges and in the ʿAyn al-Azraq oasis. Hares, jackals, foxes, wildcats, hyenas, wolves, gazelles, blind mole rats, mongooses, and a few leopards also inhabit the area. Centipedes, scorpions, and various types of lizards are found as well. Birds include the golden eagle and the vulture, while wild fowl include the pigeon and the partridge.

People

Ethnic groups

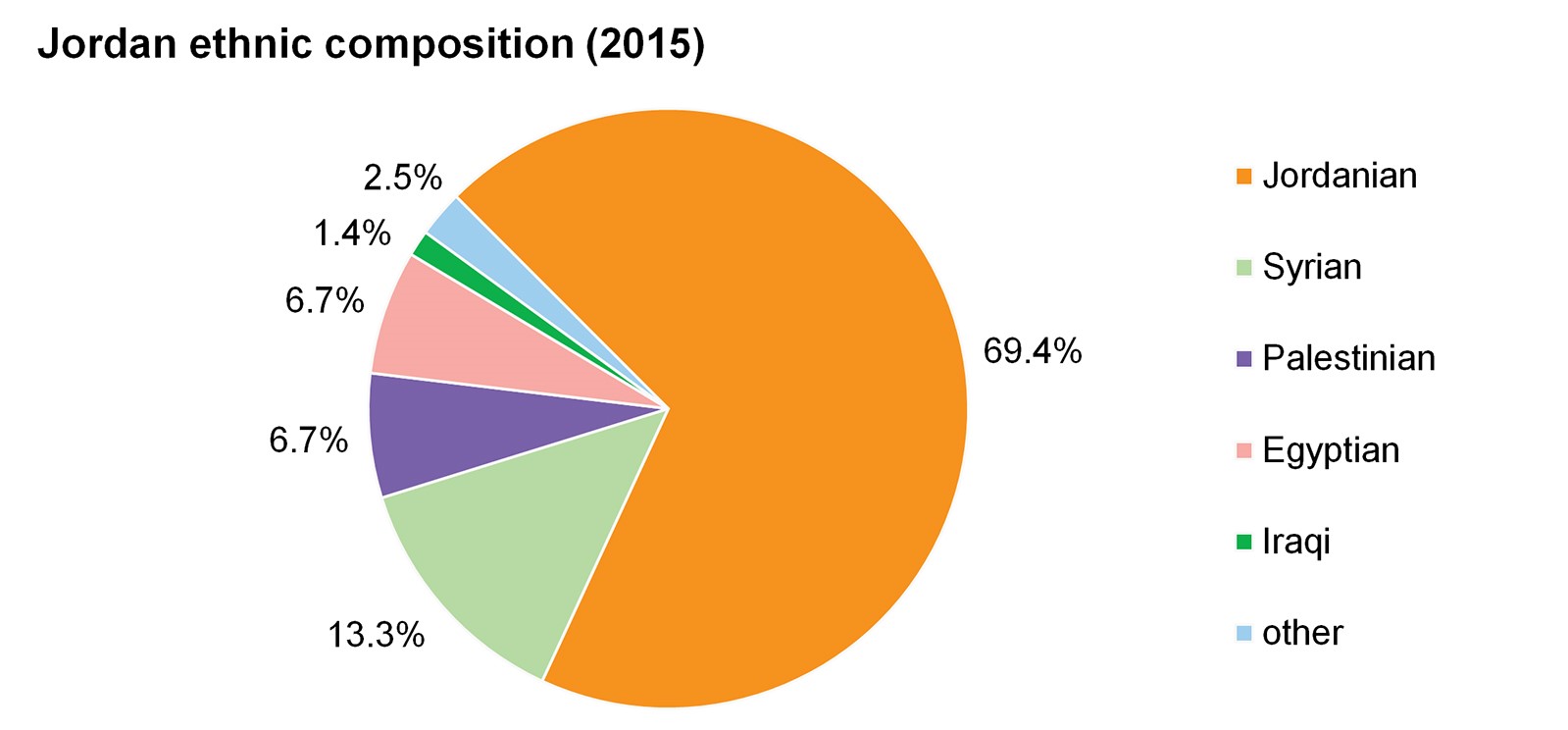

The overwhelming majority of the people are Arabs, principally Jordanians and Palestinians; there is also a significant minority of Bedouin, who were by far the largest indigenous group before the influx of Palestinians following the Arab-Israeli wars of 1948–49 and 1967. Jordanians of Bedouin heritage remain committed to the Hashemite regime, which has ruled the country since 1923, despite having become a minority there. Although the Palestinian population is often critical of the monarchy, Jordan is the only Arab country to grant wide-scale citizenship to Palestinian refugees. Other minorities include a sizeable number of Syrian refugees who fled to Jordan because of the Syrian Civil War, as well as a number of Iraqis who fled to Jordan as a result of the Persian Gulf War and Iraq War. There are also smaller Circassian (known locally as Cherkess or Jarkas) and Armenian communities. A small number of Turkmen (who speak either an ancient form of the Turkmen language or the Azeri language) also reside in Jordan.

The indigenous Arabs, whether Muslim or Christian, used to trace their ancestry from the northern Arabian Qaysī (Maʿddī, Nizārī, ʿAdnānī, or Ismāʿīlī) tribes or from the southern Arabian Yamanī (Banū Kalb or Qaḥṭānī) groups. Only a few tribes and towns have continued to observe this Qaysī-Yamanī division—a pre-Islamic split that was once an important, although broad, source of social identity as well as a point of social friction and conflict.

Languages

Nearly all the people speak Arabic, the country’s official language. There are various dialects spoken, with local inflections and accents, but these are mutually intelligible and similar to the type of Levantine Arabic spoken in parts of Palestine, Lebanon, and Syria. There is, as in all parts of the Arab world, a significant difference between the written language—known as Modern Standard Arabic—and the colloquial, spoken form. The former is similar to Classical Arabic and is taught in school. Most Circassians have adopted Arabic in daily life, though some continue to speak Adyghe (one of the Caucasian languages). Armenian is also spoken in pockets, but bilingualism or outright assimilation to the Arabic language is common among all minorities.

Religion

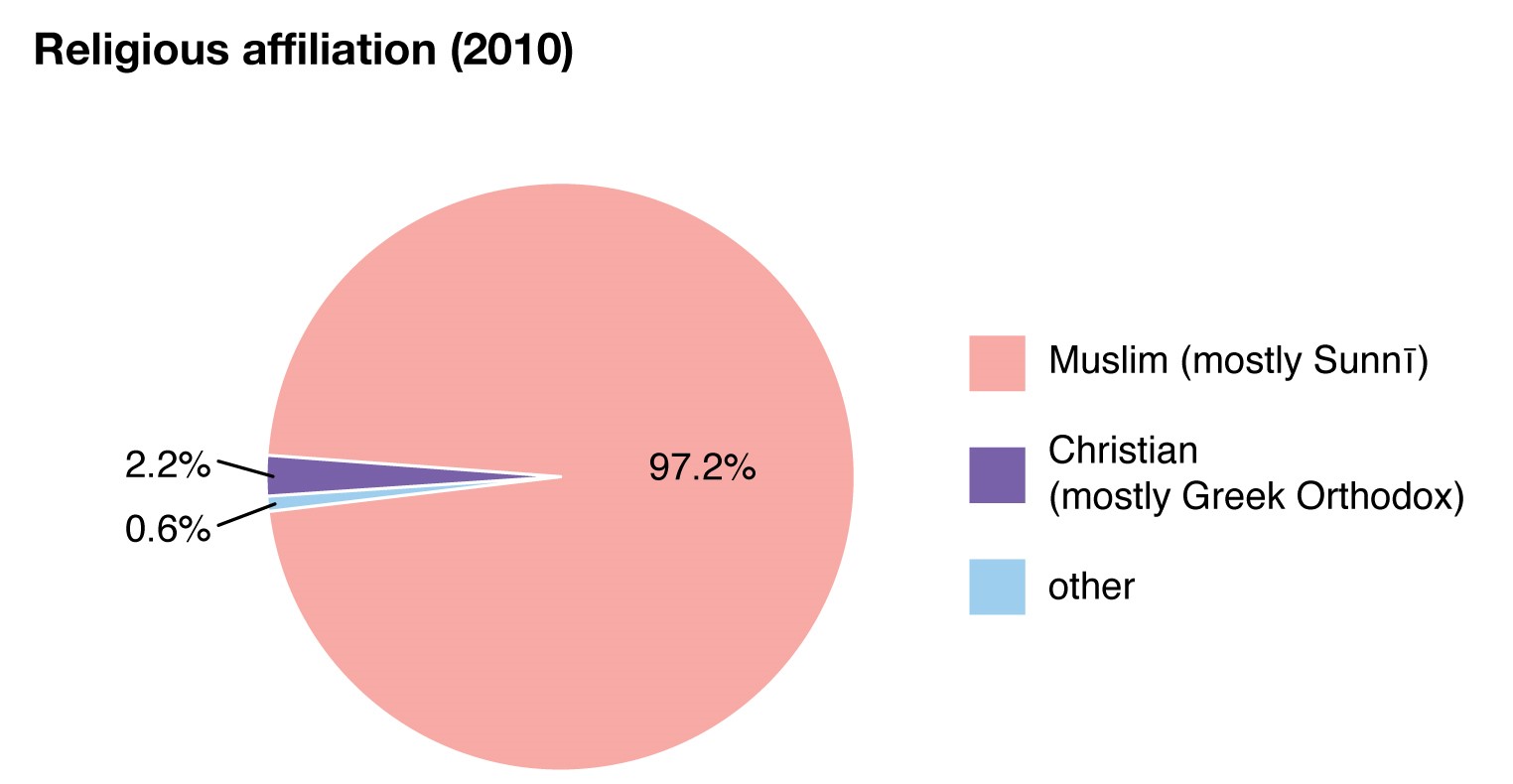

Virtually the entire population is Sunni Muslim; Christians constitute most of the rest, of whom two-thirds adhere to the Greek Orthodox church. Other Christian groups include the Greek Catholics, also called the Melchites, or Catholics of the Byzantine rite, who recognize the supremacy of the Roman pope; the Roman Catholic community, headed by a pope-appointed patriarch; and the small Syrian Orthodox Patriarchate of Antioch, or Syrian Jacobite Church, whose members use Syriac in their liturgy. Most non-Arab Christians are Armenians, and the majority belong to the Gregorian, or Armenian, Orthodox church, while the rest attend the Armenian Catholic Church. There are several Protestant denominations representing communities whose converts came almost entirely from other Christian sects.

The Druze, an offshoot of the Ismāʿīlī Shiʿi sect, number a few hundred and reside in and around Amman. About 1,000 Bahāʾī—who in the 19th century also split off from Shiʿi Islam—live in Al-ʿAdasiyyah in the Jordan Valley. The Armenians, Druze, and Bahāʾī are both religious and ethnic communities. The Circassians are mostly Sunni, and they along with the closely related Chechens (Shīshān)—a group numbering about 1,000, who are descendants of 19th-century immigrants from the Caucasus Mountains—make up the most important non-Arab minority.

Economy of Jordan

Although Jordan’s economy is relatively small and faces numerous obstacles, it is comparatively well diversified. Trade and finance combined account for nearly one-third of Jordan’s gross domestic product (GDP); transportation and communication, public utilities, and construction represent one-fifth of total GDP, and mining and manufacturing constitute nearly that proportion. Remittances from Jordanians working abroad are a major source of foreign exchange.

However, although Jordan’s economy is ostensibly based on private enterprise, services—particularly government spending—account for about one-fourth of GDP and employ roughly one-third of the workforce. In addition, Jordan has increasingly been plagued by recession, debt, and unemployment since the mid-1990s, and the small size of the Jordanian market, fluctuations in agricultural production, a lack of capital, and the presence of large numbers of refugees have made it necessary for Jordan to continue to seek foreign aid. The Jordanian government has been slow to implement privatization. Despite efforts by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank to boost the private sector—including agreements to write off the country’s external debt and loans from the World Bank designed to revitalize Jordan’s economy—it was only in 1999 that the government began introducing a number of economic reforms. These efforts included Jordan’s entry into the World Trade Organization (in 2000) and the partial privatization of some state-owned enterprises.

Perhaps most importantly, Jordan’s geographic location has made it and its economy highly vulnerable to political instability in the region. The Jordanian economy was resilient and growing before the Six-Day War of June 1967, and the West Bank, prior to its occupation by Israel during that conflict, contributed about one-third of Jordan’s total domestic income. Economic growth continued after 1967 at a slower pace but was revitalized by a series of state economic plans. Trade increased between Jordan and Iraq during the Iran-Iraq War (1980–88), because Iraq required access to Jordan’s port of Al-ʿAqabah. Jordan initially supported Iraqi president Saddam Hussein when Iraq occupied Kuwait during the Persian Gulf War, but it eventually agreed to the United Nations’ trade sanctions against Iraq, its principal trading partner, and thereby put its whole economy in jeopardy. External emergency aid helped Jordan weather the crisis, and the economy was boosted by the sudden influx of Palestinians from Kuwait in 1991, many of whom brought in capital. During 2003 the construction industry recovered with the arrival of many thousands of people fleeing Iraq, and Jordan became a major service centre for those working to reconstruct that country. Despite the support of the government for IMF and World Bank plans to increase the private sector, the state remains the dominant force in Jordan’s economy.

Agriculture

Only a tiny fraction of Jordan’s land is arable, and the country imports some foodstuffs to meet its needs. Wheat and barley are the main crops of the rain-fed uplands, and irrigated land in the Jordan Valley produces citrus and other fruits, potatoes, vegetables (tomatoes and cucumbers), and olives. Pastureland is limited; although artesian wells have been dug to increase its area, much former pasture area has been turned over to the cultivation of olive and fruit trees, and large areas have been degraded to the point that they can barely support livestock. Sheep and goats are the most important livestock, but there are also some cattle, camels, horses, donkeys, and mules. Poultry is also kept.

Resources and power

Mineral resources include large deposits of phosphates, potash, limestone, and marble, as well as dolomite, kaolin, and salt. More recently discovered minerals include barite (the principal ore of the metallic element barium), quartzite, gypsum (used as a fertilizer), and feldspar, and there are unexploited deposits of copper, uranium, and shale oil. Although the country has no significant oil deposits, modest reserves of natural gas are located in its eastern desert. In 2003 the first section of a new pipeline from Egypt began delivering natural gas to Al-ʿAqabah.

Virtually all electric power in Jordan is generated by thermal plants, most of which are oil-fired. The major power stations are linked by a transmission system. By the early 21st century the government had completed a program to link the major cities and towns by a countrywide grid.

Beginning in the final decades of the 20th century, access to water became a major problem for Jordan—as well as a point of conflict among states in the region—as overuse of the Jordan River (and its tributary, the Yarmūk River) and excessive tapping of the region’s natural aquifers led to shortages throughout Jordan and surrounding countries. In 2000 Jordan and Syria secured funding for constructing a dam on the Yarmūk River that, in addition to storing water for Jordan, would also generate electricity for Syria. Construction of the Waḥdah (“Unity”) Dam began in 2004.

Manufacturing

Manufacturing is concentrated around Amman. The extraction of phosphate, petroleum refining, and cement production are the country’s major heavy industries. Food, clothing, and a variety of consumer goods also are produced.

Finance

The Central Bank of Jordan (Al-Bank al-Markazī al-Urdunī) issues the dinar, the national currency. There are many national and foreign banks in addition to credit institutions. The government has participated with private enterprise in establishing the largest mining, industrial, and tourist firms in the country and also owns a significant share of the largest companies. The Amman Stock Exchange (Būrṣat ʿAmmān; formerly the Amman Financial Market) is one of the largest stock markets in the Arab world.

Trade

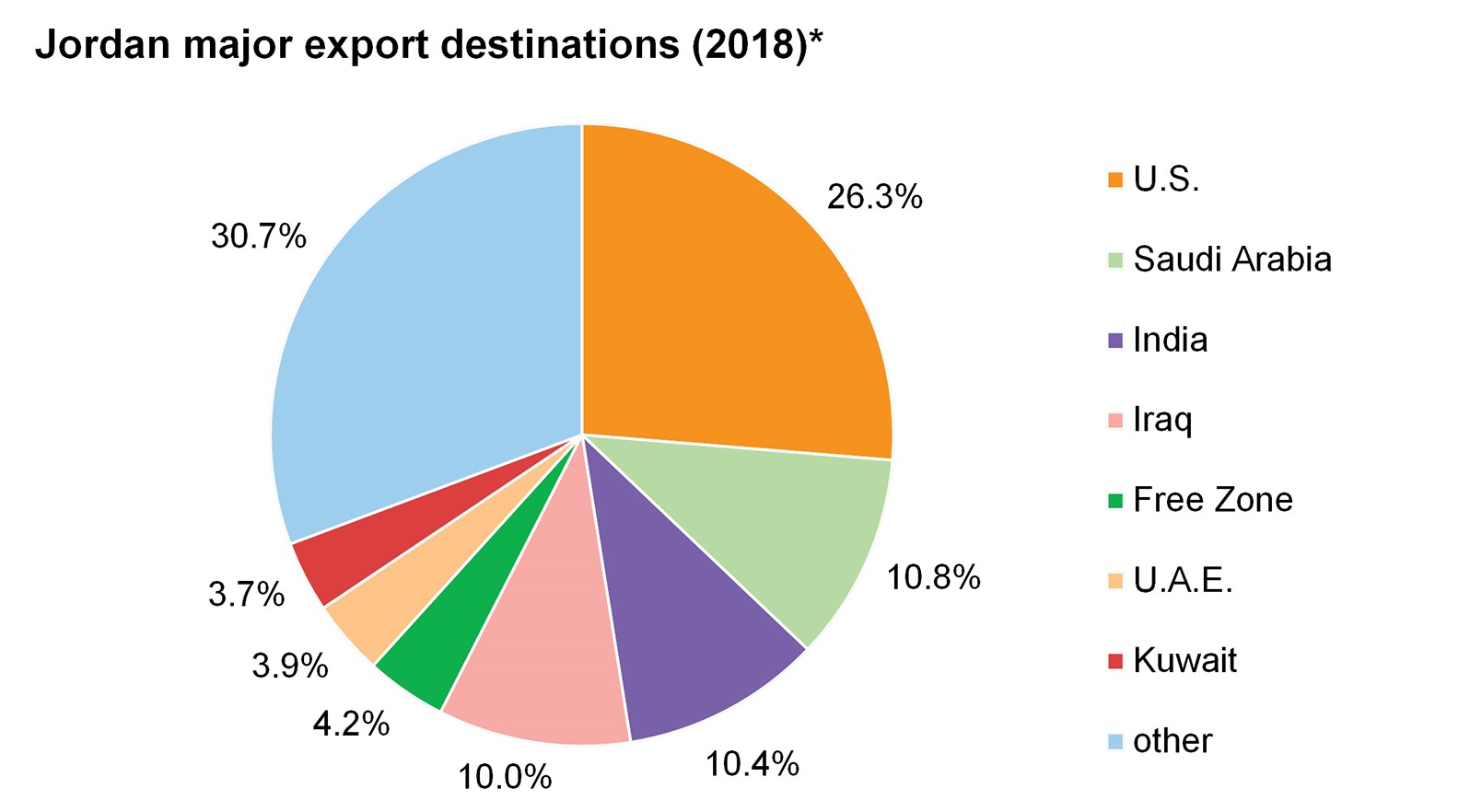

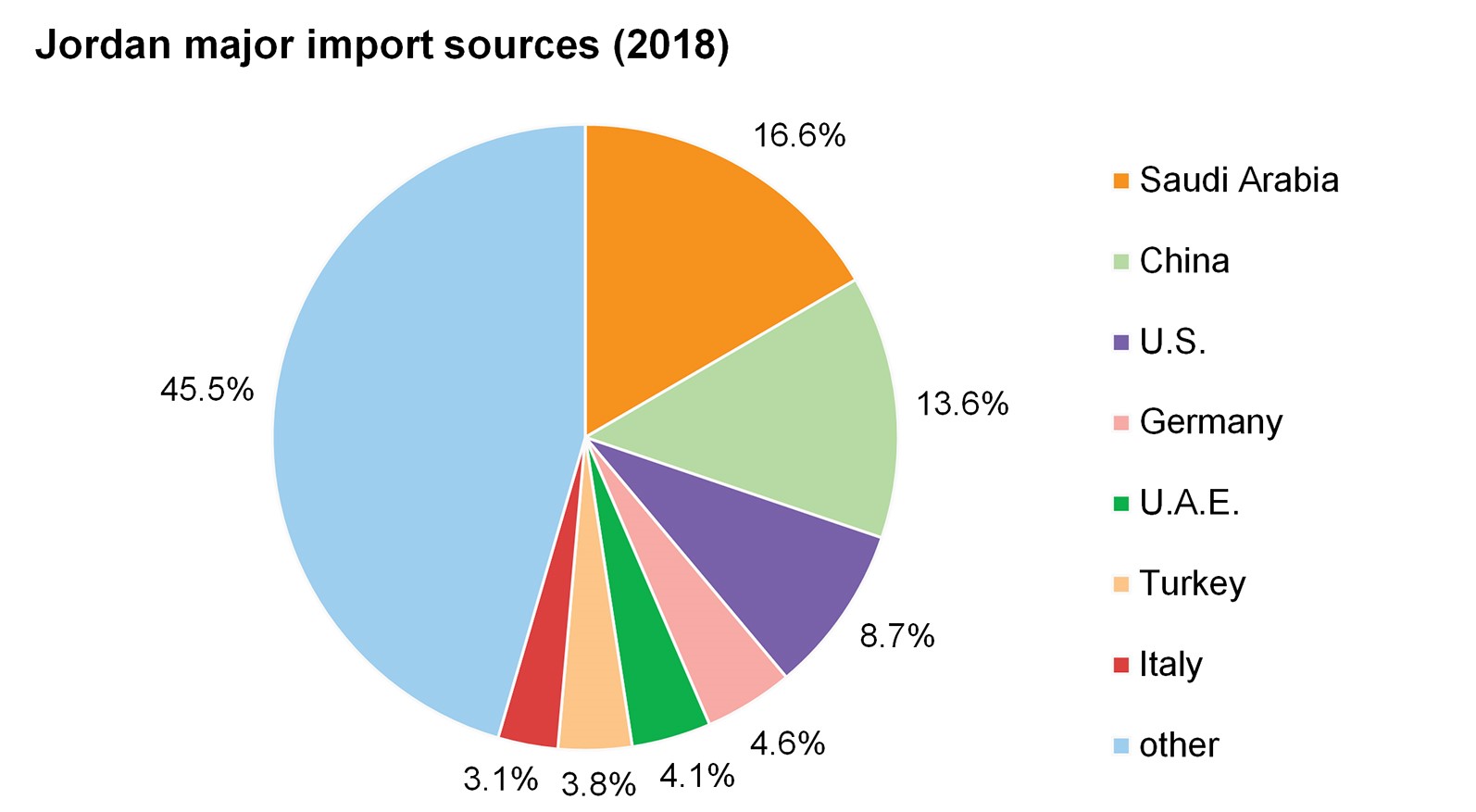

Jordan’s primary exports are clothing, chemicals and chemical products, and potash and phosphates; the main imports are machinery and apparatus, crude petroleum, and food products. Major sources of imports are Saudi Arabia, the United States, China, and the European Union (EU). Major destinations for exports are the United States, Iraq, and Saudi Arabia. In 2000 Jordan signed a bilateral free trade agreement with the United States. The value of exports has been growing, but it does not cover that of imports; the deficit is financed by foreign grants, loans, and other forms of capital transfers. Although Jordan’s trade deficit has been large, it has been offset somewhat by revenue from tourism, remittances sent by Jordanians working abroad, earnings from foreign investments made by the central bank, and subsidies from other Arab and non-Arab governments.

Services

Services, including public administration, defense, and retail sales, form the single most important component of Jordan’s economy in both value and employment. The country’s vulnerable geography has led to high military expenditures, which are well above the world average.

The Jordanian government vigorously promotes tourism, and the number of tourists visiting Jordan has grown dramatically since the mid-1990s. Visitors come mainly from the West to see the old biblical cities of the Jordan Valley and such wonders as the ancient city of Petra, designated a World Heritage site in 1985. Income from tourism, mostly consisting of foreign reserves, has become a major factor in Jordan’s efforts to reduce its balance-of-payments deficit.

Labour and taxation

Jordan has also lost much of its skilled labour to neighbouring countries—as many as 400,000 people left the kingdom in the early 1980s—although the problem has eased somewhat. This change is a result both of better employment opportunities within Jordan itself and of a curb on foreign labour demands by the Persian Gulf states.

The majority of the workforce is men, with women constituting roughly one-seventh of the total. The government employs nearly half of those working. About one-seventh of the population is unemployed, although income per capita has increased. Labour unions and employer organizations are legal, but the trade-union movement is weak; this is partly offset by the government, which has its own procedures for settling labour disputes.

About half of the government’s revenue is derived from taxes. Even though the government has made a great effort to reform the income tax, both to increase revenue and to redistribute income, revenue from indirect taxes continues to exceed that from direct taxes. Tax measures have been adopted to increase the rate of savings necessary for financing investments, and the government has implemented tax exemptions on foreign investments and on the transfer of foreign profits and capital.

Transportation and telecommunications

Jordan has a main, secondary, and rural road network, most of which is hard-surfaced. This roadway system, maintained by the Ministry of Public Works and Housing, not only links the major cities and towns but also connects the kingdom with neighbouring countries. One of the main traffic arteries is the Amman–Jarash–Al-Ramthā highway, which links Jordan with Syria. The route from Amman via Maʿān to the port of Al-ʿAqabah is the principal route to the sea. From Maʿān the Desert Highway passes through Al-Mudawwarah, linking Jordan with Saudi Arabia. The Amman-Jerusalem highway, passing through Nāʿūr, is a major tourist artery. The government-operated Hejaz-Jordan Railway extends from Darʿā in the north via Amman to Maʿān in the south. The Aqaba Railway Corporation operates a southern line that runs to the port of Al-ʿAqabah and connects to the Hejaz-Jordan Railway at Baṭn al-Ghūl. Rail connections also join Darʿā in the north with Damascus, Syria.

Royal Jordanian is the country’s official airline, offering worldwide service. Queen Alia International Airport near Al-Jīzah, south of Amman, opened in 1983. Amman and Al-ʿAqabah have smaller international airports.

In 1994 Jordan introduced a program to reform its telecommunication system. The government-owned Jordan Telecommunications Corporation, the sole service provider, had been unable to meet demand or provide adequate service, particularly in rural areas; it was privatized in 1997. Since then, the use of cellular telephones has mushroomed, far outstripping standard telephone use. In addition, Internet use has grown dramatically.

Government and society

Constitutional framework

The 1952 constitution is the most recent of a series of legislative instruments that, both before and after independence, have increased executive responsibility. The constitution declares Jordan to be a constitutional, hereditary monarchy with a parliamentary form of government. Islam is the official religion, and Jordan is declared to be part of the Arab ummah (“nation”). The king remains the country’s ultimate authority and wields power over the executive, legislative, and judicial branches. Jordan’s central government is headed by a prime minister appointed by the king, who also chooses the cabinet. According to the constitution, the appointments of both prime minister and cabinet are subject to parliamentary approval. The cabinet coordinates the work of the different departments and establishes general policy.

Jordan’s constitution provides for a bicameral National Assembly (Majlis al-Ummah), with a Senate (Majlis al-Aʿyan) as its upper chamber, and a House of Representatives (Majlis al-Nuwwāb) as its lower chamber. The aʿyan (“notables”) of the Senate are appointed by the king for four-year terms; elections for the nuwwāb (“deputies”) of the House of Representatives, scheduled at least every four years, frequently have been suspended. A small number of seats in the House of Representatives are reserved for Christians and Circassians. The ninth parliament, elected in 1965, was prorogued several times before being replaced in 1978 by the National Consultative Council, an appointed body with reduced power that debates government programs and activities. The parliament was reconvened, however, in a special session called in January 1984. Since then the parliament has been periodically suspended: from 1988, when Jordan severed its ties with the West Bank, until 1989 and from August until November 1993, when the country held its first multiparty elections since 1956. In 2001 the king dissolved the Majlis al-Nuwwāb to reformulate the electoral system; new deputies were elected in 2003.

Local government

Jordan is divided into 12 administrative muḥāfaẓāt (governorates), which in turn are divided into districts and subdistricts, each of which is headed by an official appointed by the minister of the interior. Cities and towns each have mayors and partially elected councils.

Justice

The judiciary is constitutionally independent, though judges are appointed and dismissed by royal irādah (“decree”) following a decision made by the Justices Council. There are three categories of courts. The first category consists of regular courts, including those of magistrates, courts of first instance, and courts of appeals and cassation in Amman, which hear appeals passed on from lower courts. The constitution also provides for the Diwān Khāṣṣ (Special Council), which interprets the laws and passes on their constitutionality. The second category consists of Sharīʿah (Islamic) courts and other religious courts for non-Muslims; these exercise jurisdiction over matters of personal status. The third category consists of special courts, such as land, government, property, municipal, tax, and customs courts.

Political process

Jordanians 18 years of age and older may vote. Political parties were banned before the elections in 1963, however. Between 1971 and 1976, when it was abolished, the Arab National Union (originally called the Jordanian National Union) was the only political organization allowed. Although not a political party, the transnational Muslim Brotherhood continued, with the tacit approval of the government, to engage in socially active functions, and it captured over one-fourth of the lower house in the 1989 election. In 1992 political parties were legalized—as long as they acknowledged the legitimacy of the monarchy. Since then, the brotherhood has maintained a significant minority presence in Jordanian politics through its political arm, the Islamic Action Front.

Security of Jordan

Although their political influence has now diminished, the Bedouin, traditionally a martial desert people, still form the core of Jordan’s army and occupy key positions in the military. Participation in the military is optional, and males can enter service at age 17. The Jordanian armed forces include an army and an air force equipped with sophisticated jet aircraft; it developed from the Arab Legion. There is also a small navy that acts as a coast guard. The king is commander in chief of the armed forces.

Health and welfare

The country’s infant mortality rate is lower than those of several other countries in the region. Most infectious diseases have been brought under control, and the number of physicians per capita has grown rapidly. Comprehensive health facilities are operated by the government, but hospitals are found only in major urban centres. A national health insurance program covers medical, dental, and eye care at a modest cost; service is provided free to the poor. Welfare services were private until the mid-1950s, when the government assumed responsibility. Besides supervising and coordinating social and charitable organizations, the ministry administers welfare programs.

Housing

The housing situation has remained critical despite continuing construction. Surveys conducted in Amman and the eastern Jordan Valley show that most households live in one-room dwellings. The Housing Corporation and the Jordan Valley Authority build units for low-income families, and urban renewal projects in Amman and Al-Zarqāʾ have provided new and renovated units. Housing outside of the cities and major towns remains austere, and a small number of Bedouin still live in their traditional black tents.

Education

The great majority of the population is literate, and more than half have completed secondary education or higher. Jordan has three types of schools—government schools, private schools, and the UNRWA schools that have been set up for Palestinian refugee children. Schooling consists of six years of elementary, three years of preparatory, and three years of secondary education. The Ministry of Education supervises all schools and establishes the curricula, teachers’ qualifications, and state examinations; it also distributes free books to students in government schools and enforces compulsory education to the age of 14. The majority of the students attend government schools. Jordan’s oldest institutions of higher learning include the University of Jordan (1962), Yarmūk University (1976), and Muʾtah University (1981). Many new universities were established in the 1990s. In addition to Khadduri Agricultural Training Institute, there are agricultural secondary schools as well as a number of vocational, labour, and social affairs institutes, a Sharīʿah legal seminary, and nursing, military, and teachers colleges.

Daily life and social customs

Jordan is an integral part of the Arab world and thus shares a cultural tradition common to the region. The family is of central importance to Jordanian life. Although their numbers have fallen as many have settled and adopted urban culture, the rural Bedouin population still follows a more traditional way of life, preserving customs passed down for generations. Village life revolves around the extended family, agriculture, and hospitality; modernity exists only in the form of a motorized vehicle for transportation. Urban-dwelling Jordanians, on the other hand, enjoy all aspects of modern, popular culture, from theatrical productions and musical concerts to operas and ballet performances. Most major towns have movie theatres that offer both Arab and foreign films. Younger Jordanians frequent Internet cafés in the capital, where espresso is served at computer terminals.

The country’s cuisine features dishes using beans, olive oil, yogurt, and garlic. Jordan’s two most popular dishes are musakhkhan, chicken cooked with sumac and onions and placed over clay-oven flatbread, and mansaf, lamb or mutton and rice with a yogurt sauce, which are both served on holidays and on special family occasions. Daily fare includes khubz (flatbread) with vegetable dips, grilled meats, and stews, served with sweet tea or coffee flavoured with cardamom.

Holidays that are celebrated in the kingdom include the Prophet Muhammad’s birthday (mawlid), the two ʿīds (festivals; Eid al-Fitr and Eid al-Adha), and other major Islamic festivals, along with secular events such as Independence Day and the birthday of the late King Hussein.

The arts of Jordan

Both private and governmental efforts have been made to foster the arts through various cultural centres, notably in Amman and Irbid, and through the establishment of art and cultural festivals throughout the country. Modernity has weakened the traditional Islamic injunction against the depiction of images of humans and animals; thus, in addition to traditional architecture, decorative design, and various handicrafts, it is possible to find non-utilitarian forms of both representational and abstract painting and sculpture. Elaborate calligraphy and geometric designs often enhance manuscripts and mosques. As in the rest of the region, the oral tradition is prominent in literary expression. Jordan’s most famous poet, Muṣṭafā Wahbah al-Ṭāl, ranks among the major Arab poets of the 20th century. After World War II a number of important poets and prose writers emerged, though few have achieved an international reputation.

Traditional visual arts survive in works of tapestry, embroidery, leather, pottery, and ceramics, and in the manufacture of wool and goat-hair rugs with varicoloured stripes; singing is also important, as is storytelling. Villagers have special songs for births, circumcisions, weddings, funerals, and harvesting. Several types of dabkah (group dances characterized by pounding feet on the floor to mark the rhythm) are danced on festive occasions, while the sahjah is a well-known Bedouin dance. The Circassian minority has a sword dance and several other Cossack dances. As part of its effort to preserve local performing arts, the government sponsors a national troupe that is regularly featured on state radio and television programs.

Jordan has a small film industry, and sites within the country, such as Petra and the Ramm valley, have served as locations for major foreign productions, such as director David Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia (1962) and Steven Spielberg’s Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989).

Cultural institutions

Jordan has numerous museums, particularly in Amman. The capital is home to museums dedicated to coins, geology, stamps, Islam, Jordanian folklore, and the military. The Jordan National Gallery of Fine Arts houses a collection of contemporary Arab and Muslim paintings as well as sculptures and ceramics. The ancient ruins at Petra, Qaṣr ʿAmrah, and Umm al-Rasass near Mādāba have all been designated UNESCO World Heritage sites; there are also several archaeological museums located throughout the country.